As she takes the stage at the Super Bowl Halftime Show, I’ll be remembering the artist who defined my childhood in Colombia.

Getty Images

When I told a Colombian friend that I was writing about Shakira he shook his head as he braced himself against the New York City cold. “I haven’t really listened to Shakira since she stopped producing rock music,” he said. I told him that was exactly what I was writing about—the Shakira that few Americans know existed.

Today, Shakira is an assortment of blonde tresses, sinuous hips, and a colossal voice tucked into a lithe, five-foot-two frame. Her identity is tethered to the word ‘pop’, usually preceded by “queen,” “titan,” and outfits that sheath her body like a second skin. She graced the world with “Hips Don’t Lie” in 2006, colored the South Africa World Cup with its official anthem in 2010, and she’s produced a stream of Hot 100 hits worldwide with household names like Rihanna and Beyonce, among others. Now she’ll be performing alongside Jennifer Lopez in a sweat-soaked football stadium during America’s most-watched television event.

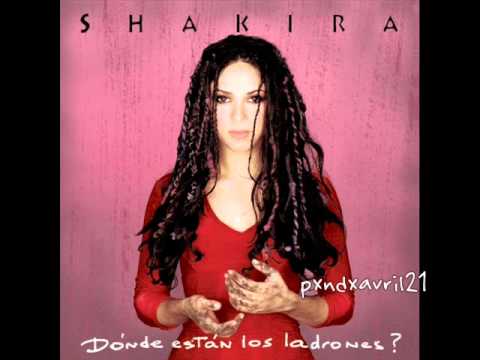

But if you scour the niche corners of YouTube, digging into albums of the ’90s, you’ll come across an altogether different artist. Instead of a blonde pop icon with fleshy body suits, you’ll find a disheveled poet with mud crusting her hands, producing ’90s alt-rock miles away from the reggaeton collabs and pop bangers that awarded her a spot in the 54th Super Bowl.

This is the Shakira of my Colombian childhood, back when I was five years old and Bogota trickled into the year 2000. Her mercurial hair was as dynamic as her music, one day a weeping black that melted into a burgundy red, another day braids woven with baby blue and ruddy fuchsia threads. Leather pants tucked into clunky black boots that vibrated against the floor as she strummed her guitar and blew life into a harmonica. Her soft-spoken Barranquilla accent contrasted the heavy eyeliner cradling her eyes. She was a rocker, yes. But beneath her gritty layers laid a soulful intelligence that held her country, and perhaps all of Latin America, in the palm of her hands.

What made Shakira so special was that her music added optimism and unity to a nation that was breaking at the seams. Colombia in the ’90s was a bed of political turmoil. Even as Pablo Escobar’s drug cartel slowly dissolved, communist guerillas continued displacing families in the countryside, cultivating cocaine, and kidnapping the rich in purported Robin Hood endeavors to return money to the masses. Violence drove out an exodus of families to cities like Miami.

But apart from the occasional bomb and the fear of being kidnapped during road trips through the guerrilla-infested highways, life moved on—and Shakira’s multi-generational appeal rendered her a constant in the Colombian zeitgeist of the ’90s. Her songs played on Walkmans during school bus rides, on the radio during barbecues, in restaurants serving arepas or fancy fusion cuisine. She was the motivational cornerstone for perseverance, as my mother was unfailingly keen on reminding me: “Shakira wasn’t accepted into her school choir because the nuns thought she sounded like a goat. Look at her now.” Her music seeped into small, ordinary moments whose significance lay in the mood and external events engulfing our lives.

Shakira fueled Colombia’s pride. Journalists praised her, politicians saw her as a true example for her generation, and Colombia’s national newspaper nominated her for Person of the Year, an irreverent choice that rejected the daily violence eclipsing our lives. Unlike the many politicians or entrepreneurs dotting the Colombian landscape, she gave us hope. Her triumph was not simply a personal achievement, but a feat that could make us proud of who we were and where we were from.

There’s a reason Shakira was Gen X’s muse as it unwinded into adulthood during the ’90s. Her words brimmed with a refined intelligence, weaving references of Roman emperors, Renaissance artists, and classical architecture with social commentary and ruminations on love. She voiced realities that many identified with but had never put into words, rendering her songs “popular wisdom” that also served as dating advice. Indeed, “there’s no worse blind man than he who does not want to see,” and “every new broom always sweeps well,” as she sang in “Si te vas.” The first song she ever wrote was titled “Tus Gafas Oscuras” (1991) and addressed the grief that her father was “carrying” and trying to hide behind his sunglasses. Even at eight years old, she had a way of unearthing the metaphors of life and transposing them into art.

As she siphoned her deepest thoughts into the collective consciousness, Shakira’s melodies beckoned those of us too young to understand the depth in her words. “Si Te Vas” kindled a heartbroken strength while “Inevitable” seeped you in its bold melancholy and “Un Poco de Amor” enveloped you in a feel-good high. She had a knack for picking you up during rough times and helping you forget, while concomitantly providing a berth in which to seep into your emotions and find solace in immersing yourself in them entirely.

The thing is, Shakira’s music isn’t like a song that reawakens a defining moment, a tender aroma, or an emotion emblazoning a given point in time. Hers is a heftier, full-bodied nostalgia that threaded years of my life. I associate her with the scuffed leather of my father’s rickety BMW, the kindergarten love-letters I never sent, and family gatherings where I’d shake my five-year-old limbs as if I could slash the air with my hip bones. She followed the wary months of my grandmother’s kidnapping and the misty mornings when we sliced the Colombian mountains on horseback. I can’t associate her music with one specific moment because she was present during them all.

When she began touring worldwide in the early aughts, Shakira became an international symbol for Colombia that wasn’t Pablo Escobar or bottomless mines of cocaine. In 2002, her first English-language album Laundry Service earned her profiles in Rolling Stone and media coverage corroborating her strategic crossover into the US music scene. By the time Hips Don’t Lie ranked 5th on Billboard’s Hot 100 in 2006, Colombian newspapers were calling her “our Shakira,” and “our star and best ambassador to the world,” holding on to the symbolic unity of Shakira and Colombia even as the two grew geographically estranged. She paved a road explored by various Colombian artists of today: J Balvin and Maluma as they produce hit records, Camilo’s immersive “Tutu”, and Juanes’ collaboration with heartthrob Sebastian Yatra. Every one of them is a pillar that has shaken the world with their talent, dispelling ideas of a Colombia too dangerous, too bleak, and incarcerated in a history that for decades mired its beauty in the eyes of the outside world.

Of course, Shakira’s catapult to global stardom also meant catering to a greater audience. Where she once questioned her “hopes turning into fears and her dreams into plans,” she now documented a She-Wolf (2009) “sitting across the bar, staring right at her prey,” and seeing that things were going well, eventually getting her way. Songs that asked God what language he spoke transmuted into songs about how she wanted a man who was a “prince in the streets, but savage and dangerous in the sheets.” Her metamorphosis into a Britney-esque superstar wasn’t just reflected in her new hairstyle. It was apparent in the lyrics and melodies that Colombia had fallen in love with, and that she left behind.

All you need is a Spanish translator to witness the slew of comments on YouTube longing for the Shakira of the past. Maybe her musical pivot lies in the passage of time, an inevitable growth reminiscent of Taylor Swift’s country evolution to full-blown pop phenomenon. And yet, you can still find glimmers of the old Shakira in her newer work. Tango, reggaeton, and trap also seep into the mix, a myriad genres that somehow manage to rank the charts worldwide. Shakira’s ability to harness and elicit a wide stream of emotions still exists. It’s simply that the songs of the past have stayed in the past, while Shakira herself has evolved.

Today, my Zen sister, artistically-versed mother, and unflappable dad belt out Shakira’s old songs in their entirety during road trips. No landscape is spared from our grating vocal chords: not the Holstein cows grazing the countryside, or the graffitied grunge of Bogota’s brick facades, nor the mountainous highways that sink into the clouds. But I would be lying if I said that her new collabs don’t star in our everyday, too. Her reggaeton, vallenato, and bachata evoke emblematic genres of our coffee-soiled Colombia.

During the 54th Super Bowl, Shakira will probably undulate her hips like hypnotic waves, sketching a burnished smile while moderating her voice into sandpaper, both hard and soft. The thing is, beneath Shakira’s silky tectonic hips and reggaeton musings lies a pillar of Colombia’s past, wisdom and heady rock buttressing a wealth of national pride.

Nobel Prize-winning author Gabriel Garcia Marquez once questioned the compatibility between Shakira’s power of creation and her “black braids of yesterday, the red ones of today,” and “the green ones of tomorrow.” Truth be told, I’ve always said that I miss the old Shakira, the one with the red braids and harmonica that bled life into my childhood, and ultimately, my home. Perhaps I simply miss the fond memories of my past. It just happens that Shakira and Colombia’s past seem to be endlessly intertwined.